Author Anne Garrels discusses her work as a reporter and the challenges of reporting on Russia

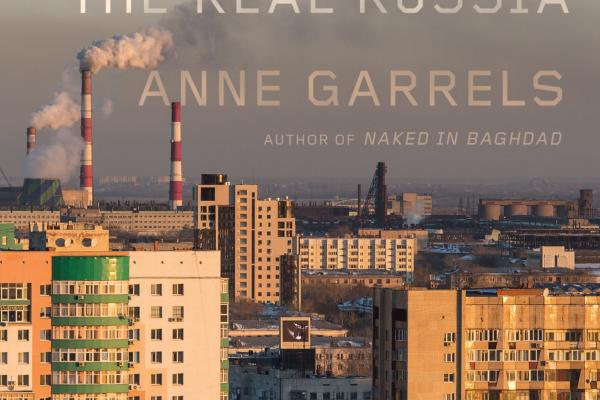

Anne Garrels, author of Naked in Baghdad and Putin Country: A Journey into the Real Russia and former NPR correspondent, will visit Columbus and the campus of Ohio State on April 6 and 7 to deliver the keynote address of the 2017 Midwest Slavic Conference, organized by the Center for Slavic and East European Studies (CSEES) and the Midwest Slavic Association.

Garrels’ most recent book, Putin Country, was 20 years in the making. Garrels started working as a journalist in the late 1970s and over the course of her career she spent substantial time as both a TV and radio correspondent covering the Soviet Union. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Garrels decided to undertake a new journalistic project to show what Russia was like outside of the large Moscow metropolis, illustrating life for the average Russian and what they were experiencing during the tumultuous 1990s.

Since 1993, Garrels has regularly visited the city of Chelyabinsk, Russia. Chelyabinsk is a city just to the east of the Ural Mountains and to the south of Yekaterinburg, and is the capital city of the Chelyabinsk Oblast. During the Soviet Union, the city experienced rapid industrial development, in particular during the time of the Second World War, when much industrial production was moved from the western regions of the country. Following the war, it was a “closed” region, meaning foreigners and even Soviet citizens from other regions had limited access because of several strategic and secretive industries that focused on nuclear processing or armament production that were located in the area. As Garrels describes in her first chapter, “Chaos”, with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, however, Chelyabinsk fell on hard times as its industries very quickly had to deal with the transition to a market economy, rapid decline of state subsidies, and decades of environmental pollution.

It is these experiences, impressions, and orientations that Garrels hoped to capture and that she eloquently presents in Putin Country. Her book brings to life the real world struggles that residents of Chelyabinsk, and ostensibly many residents of other similar cities and regions throughout Russia, encountered in the 1990s through a series of vignettes describing the myriad of people she has met and developed relationships with over the past two decades and how those feelings still resonate today for them politically and culturally.

As part of her keynote address, “Putin Country: A Journey into the Real Russia and the Challenges of Covering Russia”, Garrels will discuss her book and observations, as well as her broader experience working in Russia and as a journalist covering its political and cultural developments. In preparation for her talk, CSEES staff discussed with Garrels in more depth her background and experiences in Russia.

Q: How did you first become interested in Russia?

Garrels: I became interested in Russia by complete fluke. My chemistry advisor, probably realizing I had little talent for science, suggested I take Russian. He suggested it might prove useful if I pursued medicine! Well, pre-med ultimately went out the window and I was hooked on Soviet studies.

Q: How have Russians received your book?

Garrels: It’s hard to know how Russians’ overall have received the book, because it has not been published there but those who have managed to read it believe it gives an accurate overview of changing attitudes and transformations. A local historian in Chelyabinsk indeed wants to publish it now. We’ll see.

Q: When do you plan to return to Russia and Chelyabinsk?

Garrels: Should I get a visa, and that’s always iffy, I plan to go back later in the spring.

Q: Putin Country really elucidates for the reader how the average Russian who lives outside of a major city in Russia views its government. Do you see any possibilities of this changing in the short- to medium-term? Why or why not?

Garrels: There are so many “red lines” that Putin has so far managed to cross without major upheavals that it is hard to know what will or could ultimately affect his popularity. The opposition remains fragmented, and largely silenced by threats and Putin’s control of television. While the internet remains freer than you might think, most Russians continue to get their news from TV.

Q: Has the U.S. policy or government community been interested in your book? Do you believe that officials at higher levels of the U.S. government have a good understanding of the Russian government and how Russians understand their own country and the West?

Garrels: There is interest in my book by policymakers and Russian experts but thoughts of policy change have been overwhelmed by domestic intrigue, Russia’s apparent meddling and so-far unproven conspiracy theories. The US Ambassador has invited me to speak in Moscow though how long he will be in place is another question. I think that Russian watchers, focused on Moscow and their friends in the liberal intelligentsia, did not fully appreciate how traumatized Russians were by the 90s, their economic struggles, loss of identity and growing anger at what they perceived to be US insensitivity to Russian concerns. By our ignorance, I would argue that we did a great deal to promote Putin and his nationalist agenda.

Q: So much of the daily news that a Russian consumes is focused on foreign events and news. Some have posited that this is a way for the Russian government to use the media to remove attention from domestic matters. In your experience is this true and if so, why?

Garrels: There is no question that Putin has taken control of TV. Other media have been corralled by pressure. Advertisers, whether for TV or internet sites, are loathe to be associated with the opposition lest the authorities go after them with the tax police or some such. A journalist friend from Chelyabinsk had been an intrepid investigative reporter. When newspapers would no longer hire her, she created a blog. Her backers eventually were frightened off. She was repeatedly warned by un-named people over the phone that she should back off. She is now seeking asylum here.

The media, certainly focuses on the evils of US policy and leaves domestic problems largely uncovered. This is a way to shift blame, and avoid exploring the reasons for problems at home.

Q: In the book you document hardships faced by many different people in Chelyabinsk, how would you describe the mindset of the people you interview in their ability to cope with these difficulties?

Garrels: The people I have come to know over more than two decades have responded in different ways to hardships. Some have become successful, and are loathe to jeopardize their success by challenging the government. Those with money have sent their children abroad so that they have the language skills if they need to leave the country altogether. I know a few couples who have managed to have their children in the US, so they will have citizenship.

Some are persuaded that today’s hardships are necessary to make Russia stronger, and self-sufficient in food.

For those in the human rights field, life has become very difficult. They can no longer receive foreign funding. Many who I write about have since been forced to give up their efforts. Some have changed directions, working in areas that are “acceptable” to the authorities, such as helping sick orphans.

Q: What started you on the path to a career in journalism?

Garrels: After college I initially worked for a publishing house. I really had no idea what I wanted to do. My interest in Russia grew, and I managed to get a job as a researcher on a documentary about the Soviet Union. From there I went to ABC’s World News Tonight as a production assistant. Luck and my knowledge of Russian made all the difference. In 1979 my boss sent me to Moscow as the network’s correspondent , hoping that despite my inexperience, I might be able to produce better stories than other network correspondents who had no command of the language, and were dependent on their KGB translators. While print reporters had real expertise, the TV people for the most part did little more than stand on Red Square in fuzzy hats saying “TASS says”. I was terrified by the challenge and recall my first night in Moscow sobbing. Then I realized that since my apartment was undoubtedly bugged, the Soviet authorities could hear me. I went out in the cold and continued to weep..

Q: What was the switch from television reporting to radio broadcasting like?

Garrels: I became increasingly frustrated with the limitations of TV news. When I returned to the US, after I was expelled from the Soviet Union, I began to listen to NPR. I wanted the ability to report with that kind of depth. I took a huge salary cut, but never looked back. I was challenged as never before. NPR allowed me to create pictures with words and voices. Armed with only a small recorder, and working alone, I was able to do many stories that would have been difficult to do for TV. Of course technology has changed, and TV reporting need not be as intrusive as it once was, but TV news is still limited in scope.

Q: Putin Country is your second book. What made you decide to write/report in a new medium after a lengthy career in television news and radio broadcasts?

Garrels: I retired from NPR to be at home more with my husband. I was also worn out after 8 years covering Iraq. (The first book I wrote was really little more than a diary of what happened in the early days of the Iraq war). I returned to my passion – Russia. I finally had the time to go back for long stretches and continue my work in Chelyabinsk. It seemed to me that I had material that no one else was writing about – the views of Russians beyond the beltway. I tried to let them tell their evolving stories.

The keynote address is free and open to the public.

Friday, April 7 @ 7PM

Sullivant Hall, Room 220

1813 North High Street

Columbus OH 43210

please RSVP to csees@osu.edu

Further reading and listening:

NPR Fresh Air Interview with Anne Garrels “’Putin Country” Offers Glimpse Inside ‘Real’ Russia”

All Sides with Ann Fisher with Anne Garrels and Gerry Hudson, talking US-Russia relations